By using our website, you agree to the use of cookies as described in our Cookie Policy

Lessons on the Copper River Delta: A Salmon System

Lessons on the Copper River Delta: A Salmon System

Words and photos by Kate Morse

Where the mountains meet the sea—and where humpbacks swim nearby….that’s what drew me fresh from college (and the East Coast) up to Cordova, AK. I might have applied my scientific background a bit to prepare myself for the climate created by where the mountains meet the sea (RAINY!), but it wouldn’t have mattered. From my first drive across the Copper River Delta from the airport into town, I was hooked.

My background in science and passion for leading youth on outdoor educational adventures led me to work at the Prince William Sound Science Center. I couldn’t believe how lucky I was to be teaching about how glaciers carved our landscape next to an actively calving glacier, or the salmon life cycle while wading in their wetland habitat, helping students hold and measure salmon fry caught in minnow traps. While most teachers used books or web-based resources to convey these lessons, I had landed in the most incredible outdoor classroom to teach with these real-life experiences.

I think the most important lesson the Copper River offers us is how an intact and largely functioning watershed, composed of glacier-capped mountains, healthy boreal and temperate rainforests, and lakes, streams, and wetlands fed by clean water can support continued runs of wild Pacific salmon. Within their complex life cycle of migrating between salt and fresh water, juvenile salmon stagger the timing of these transitions among their “cohort”. This strategy makes the population resilient, but only if there is unimpeded access to their spawning grounds and cold, clean water and gravel of a specific size when they get there.

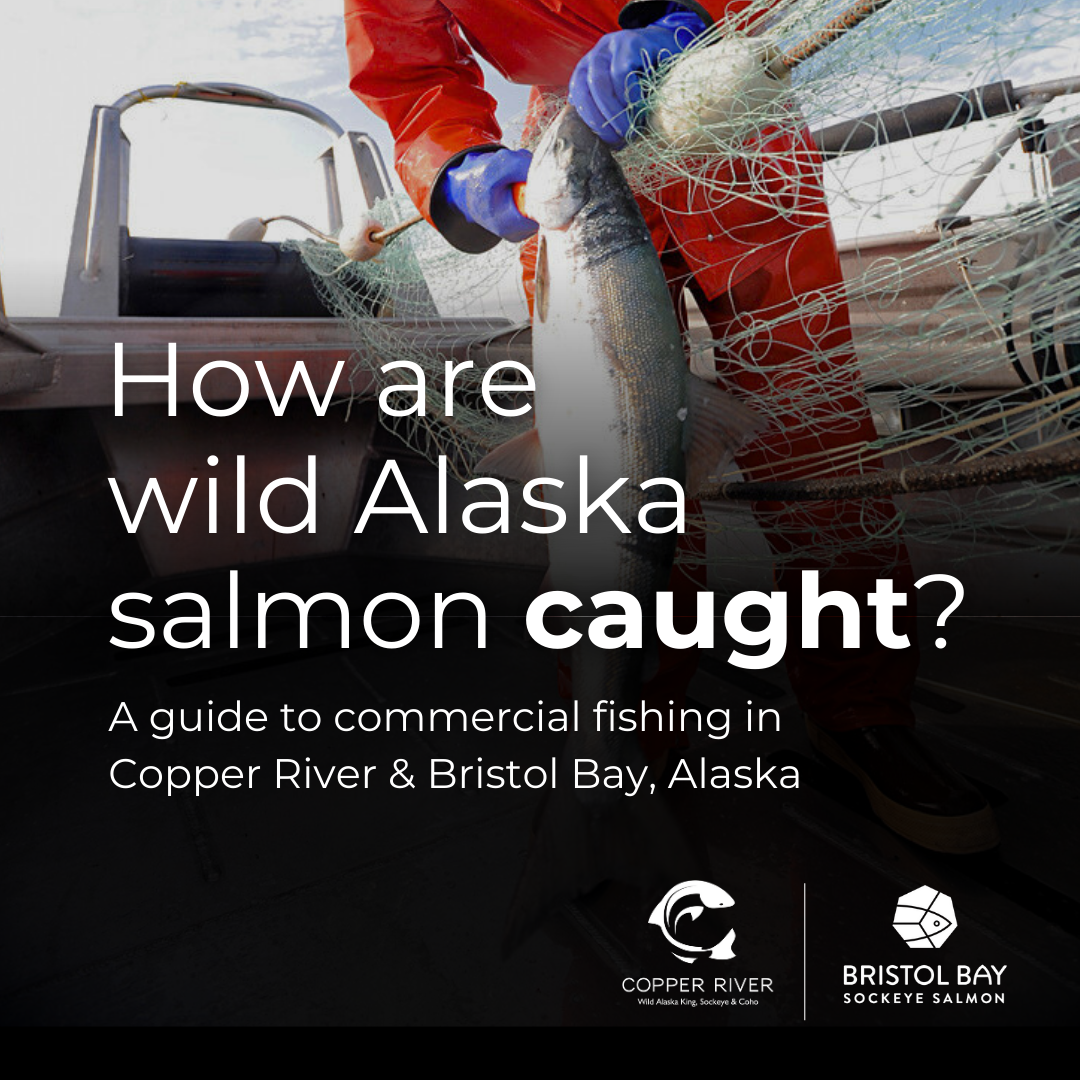

In addition to the marine-derived nutrients that adult salmon bring back to the freshwater streams when they spawn, feeding the bears, birds, and even the trees, Copper River salmon support the local economies through longstanding subsistence traditions where salmon is harvested for year-round sustenance, sport fishing business opportunities, and a commercial fishery based at the mouth of the river. Growing up on the East Coast I had a bias against commercial fisheries, being more familiar with the devastation that unsustainable fishing practices had on fish stocks along the eastern seaboard. However, it didn’t take long to learn how things were different in Alaska.

There is a fixed number of permits available, limiting the overall number of nets in the water. Fishermen can only fish during strict time periods, in specific places, and in recent years have been banned from fishing the shallower, “inside” waters, or not at all until Alaska Department of Fish and Game counts enough fish swimming past its sonar station to support upriver fisheries and spawning. There are also limitations that can be put on sportfishing and subsistence fishing as a result of low numbers returning. This “in season” management approach makes overfishing these stocks less likely.

What we’ve learned from fisheries and watersheds in the “Lower 48” is that even if fish aren’t over-exploited through fishing pressure, the loss of connectivity and habitat degradation affects salmon populations’ ability to reproduce. The loss of habitat due to water diversion, erosion, pollution, and impediments like dams or poorly installed culverts imposes devastating impacts on salmon populations. As watershed integrity erodes and water quality declines, there are fewer viable spawning sites. Fewer salmon able to spawn means the population trend line goes down.

It is these lessons that motivate me in my current work at the Copper River Watershed Project. With my peers, I am working hard to convene partners throughout the watershed to keep the watershed intact and thriving—our political boundaries as well as limited access and large distances between communities make this extra challenging. I hope to help sustain connectivity between all residents of the Copper River watershed so they see themselves as part of a larger watershed community working together to keep this amazing ecosystem functioning and support our greatest renewable resource, wild Alaska salmon.

I also want to make sure the amazing lessons we can learn from the Copper River watershed are applied to help restore other watersheds. Furthermore, I believe that keeping things as naturally functioning as possible will provide the best opportunity for salmon and the ecosystem they support to adapt in an uncertain and rapidly changing future. Sustaining healthy salmon runs is necessary to ensure that subsistence fishing traditions and the sport and commercial economies can continue for generations to come, allowing my daughters and their children to live connected by the tides and seasons to a renewable resource supported by the amazing Copper River watershed we are fortunate enough to call home.

Kate Morse is the Program Director at the Copper River Watershed Project which works to encourage stewardship of the Copper River Delta through habitat conservation, restoration and community outreach

‹ Back